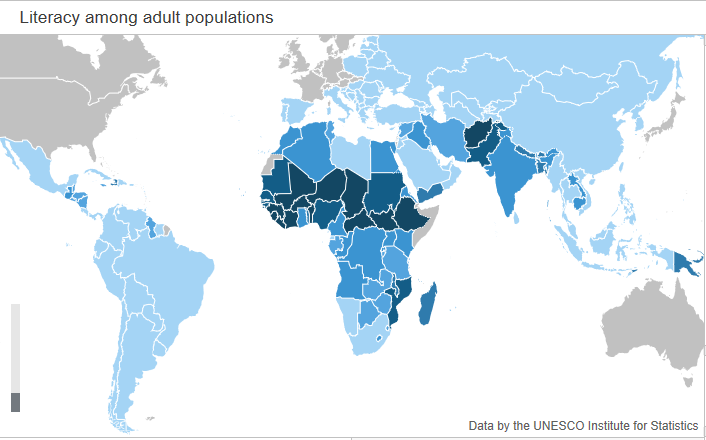

One in every seven adults worldwide is illiterate. That’s more than 750 million people who struggle with reading and writing. As well as the damage to personal dignity, illiteracy also comes at a high cost to the global economy – a study by the World Literacy Foundation put it at more than one trillion dollars in 2015.

Being illiterate equates to being trapped in poverty, having limited employment opportunities and a greater risk of poor health - not to mention a higher chance of becoming welfare-dependent. Children of uneducated parents often end up in the same situation because bringing home money for the family to survive is more critical than receiving an education.

Literacy surveys show a link between literacy rates and national wealth – literate societies are better off than societies with widespread illiteracy, and improving literacy has been observed to result in a lower share of the population living in poverty. This is why raising literacy levels, especially among women, is part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Source: Unesco eAtlas of Literacy, 2015

Targeting adult learners effectively

Typically, adult literacy initiatives have focused on the ‘three Rs’ - reading, writing and arithmetic. They are taught in a classroom setting by qualified teachers and usually take between six months to two years to complete.

Not only has this has proven to be a costly approach – programmes have also been hampered by a lack of teachers, and learners have struggled to make time to attend lessons over such an extended timeframe due to work commitments.

Now, digital technology is helping to disrupt this crucial area, with computer-based teaching making learning to read easier and faster. One of the most successful methods originates in India – home to more than a third of the world’s adult illiterate population.

The CBFL software (or Computer-Based Functional Literacy Solution for Adult Literacy, to use its full name) was developed by Tata Consultancy Services, which makes it available free of charge to government and education authorities, NGOs, corporates, and charitable organisations such as Rotary and Lions Clubs.

Source: TCS

Using technology as a leveller

CBFL is tailored to adults above 15 years of age who haven’t had any formal schooling. The lessons use multimedia technology, including animated graphics and a voiceover, to explain how letters combine to create words and meanings. The system is specially designed to run on relatively low-cost Intel 486-based computers.

The programme is based on materials from India’s National Literacy Mission and covers nine Indian languages.

The emphasis is on words rather than alphabets, taking into account the fact that adult learners already know the sounds of words, and what words denote in the real world. This is different from teaching children and means all learners need to do is connect the spoken sound with the written word.

Using the software, a student can become literate within 50 hours spread over a period of three months – a fraction of the time it would take to complete a conventional programme.

Learners will acquire a 500 word vocabulary in their own language or dialect. This is usually sufficient for everyday requirements such as reading signs, simple documents and even newspapers.

Cutting to the chase

Because the programme is multimedia-driven, it does not require trained teachers. Local people with a higher education can step in as tutors, and can be trained by TCS. This, combined with the use of cheap hardware, enables a person to become literate for around five to seven US dollars.

Source: TCS

The teacher conducts 1.5 hour classes for between 20 to25 students. Learners can work at their own pace and at times that do not conflict with their working hours. As a result, the CBFL programme has seen lower dropout rates.

Proven benefits of the course include participants being able read and sign paperwork with their name rather than their fingerprint; improved access to health, environmental and social information; and greater confidence and self-esteem.

Those who have completed the training make it clear how much literacy empowers people, giving them a level of independence and opportunities they would otherwise not have been able to attain.

Source: TCS

“Now that I can read I have learnt a lot,” says Krishnavani, an early graduate from the programme. “I can read newspapers. I know where the bus is going. I can read the electricity bill. I can take my own meter readings. Now nobody can cheat us.”

Shivalingamma, who took the programme in 2014, goes one step further: “I did not know about the injustices in our society, as I could not read or write. Through the night literacy classes organised in my village, I have learned to read newspapers as well as short story books. This has helped me to become a representative in a women’s self-help group.”

Proud of their mums

Children whose parents have learned to read take pride in their newly-acquired literacy. Understanding the impact of education also has a reverse effect, as Pamula, another graduate, highlights:

“Before, I didn’t realise the importance of education. Now all my four daughters go to school regularly. I’m also helping my children with their studies.”

In addition to the economic implications of raising literacy levels, the CBFL programme may also contribute to breaking the vicious cycle of parents setting their children up for a life in poverty by not prioritising their education.

A global impact

As of November 2016, the CBFL system had reached 315,309 people across 14 states in India. In the last few years, writing and arithmetic have been added to the curriculum.

Since 2015, the programme has also been made available in a number of Indian prisons, reaching more than 5,000 inmates to date.

Having received a series of national and international awards, the software has expanded its footprint beyond India. Programmes have been rolled out in South Africa for the Sotho language, and in Burkina Faso, where 2,000 speakers of the tribal Moore language have taken the course to date. There is also an Arabic version of the CBFL software, and TCS is in the process of developing software in Spanish.

Thanks this is very nice education for all, the world is becoming a global market if every one can speak and write. GOD BLESS YOU ALL.

Great initiative

i need it

Is there a link where we people from different country can download this software. Thanks for it.