As night falls over Kaziranga National Park in India’s Assam state, some of the world’s most endangered animals begin to stir. Some prepare to hunt, others to be hunted - the circle of life playing out in the wild.

But it is not only animals looking to make a kill. Kaziranga is a magnet for poachers, drawn by the rich rewards offered for rhino horn – a prized product worth thousands of dollars on the black market. And darkness makes the poachers’ job all the easier.

Amid the sounds of the park’s nocturnal awakening, though, a buzzing begins. Loudly at first, then quickly fading into the distance. This is the sound of a new weapon in the fight to save the rhinos: a drone taking off to begin its night-time poaching patrol.

The park is home to two thirds of the world’s one-horned rhinos and the hope is that by patrolling the skies above the animals, poaching can be significantly reduced.

It is not just rhinos set to benefit; the park is also home to many elephants, tigers and other wildlife.

Elephants from the air, Kaziranga National Park Source: TCS

The introduction of drones has been hailed as a “milestone in wildlife protection” by Kaziranga Park Director NK Vasu.

Assam Forest Minister Rockybul Hussain said this was the first time that drones had been used for wildlife protection anywhere in India.

“The UAVs will deter poachers who will now have to reckon with surveillance from air as well as on ground,” Mr Hussain said.

The minister said it would now be possible to keep an eye on the remotest parts of the 480 square kilometre park.

The deployment of the drones, coordinated by Tata Consultancy Services, followed a spate of rhino deaths at the hands of poachers.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have also been used by the WWF in nearby Chitwan National Park in Nepal, where the hunting of one-horned rhinos has been drastically reduced.

The flights are also used to find unauthorised settlements within the park, which are often associated with poaching.

Illegal settlements in Kaziranga National Park Source: TCS

Poaching is made easier by the remote nature of areas in which endangered animals often live. The vast tracts of land needed to sustain rhino and elephant populations are costly and difficult to patrol on the ground.

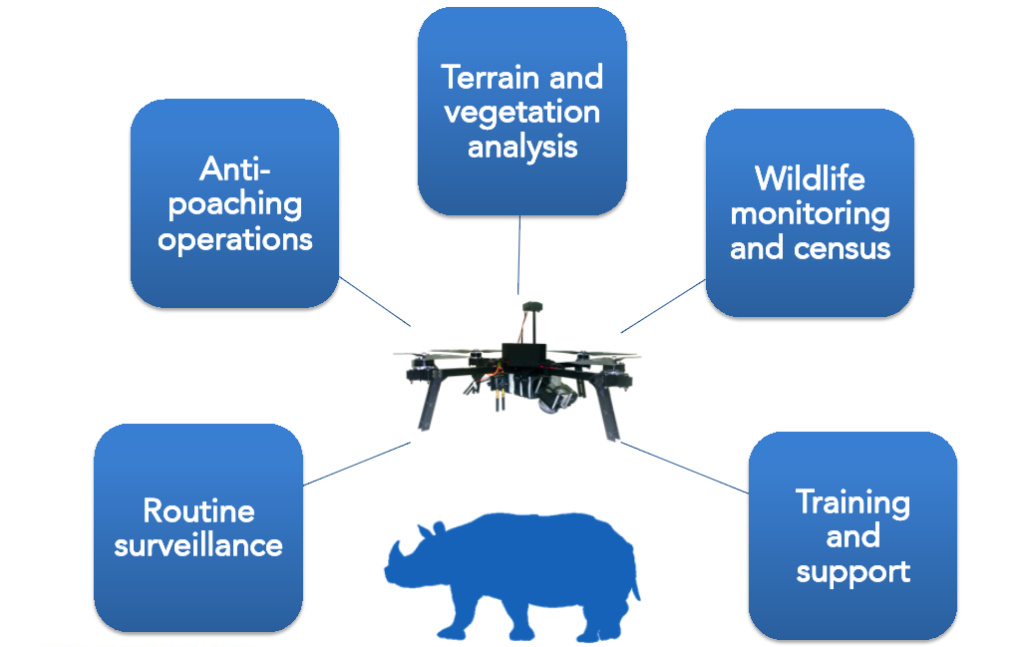

Range of uses

The drones are capable of fully autonomous flights and can carry thermal imaging and mapping equipment as well as day and night-capable video cameras. Images can be recorded on board and monitored on the ground in real time.

This means that as well as anti-poaching duties, the vehicles can be tasked with other uses - from wildlife census to vegetation analysis. Their long range and high endurance opens up difficult-to-reach areas to regular and comprehensive monitoring.

All of which helps to support and protect the vulnerable rhinos.

Drones offer unique access but are also uniquely unobtrusive. At another UAV project at Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it is elephants that are being protected.

Julie Linchant, a graduate student at the University of Liège in Belgium who has been working on the project, told the New Scientist: “Drones are very silent, so you don’t disturb animals and you can find poachers discreetly.”

Around the world drones are taking on the poachers with some considerable success. In Belize, the Wildlife Conservation Society has helped deploy them to successfully monitor a protected reef area for illegal fishing. In Indonesia, drones have been used to survey threatened orangutan habitats. And in Africa, the World Wildlife Fund is exploring the use of drones and other anti-poaching technologies with funding from Google.

Safer for everyone, except the poachers

In the past, aeroplanes and helicopters were used to protect and monitor wildlife over large areas, a costly and difficult operation. Drones are not only much cheaper, they cause less environmental damage and much less disruption to wildlife.

Their use could save many human lives too.

According to the Wildlife Society Bulletin, 60 US biologists died between 1937 and 2000 in aircraft accidents, making this by far the most common cause of death while in the field.

If a drone goes down it’s a small financial cost, nothing more.

Survey flights

Drones are also allowing greatly increased accuracy when it comes to surveying animal populations – vital when it comes to conversation work.

Monitoring bird populations Source: Rohan Clarke/Monash University

One pioneer in the field is Jarrod Hodgson at Monash University in Melbourne. He flies drones around remote Australian islands to tally native birds, like greater crested terns. His group is comparing the drone counts with those done on foot, which tend to be tough work for scientists and disrupting to the birds.

Monitoring tern a colony at Ashmore Reef in Australia Source: Rohan Clarke/Monash University

Drones for conservation

So important are drones to the future of conservation, the Indian government has put them at the heart of its new 14-year wildlife plan. The number of protected areas of land in India will rise and they will be managed using high-tech surveillance drones and centralised web-based digital equipment.

The National Wildlife Action Plan 2017-31 takes in a broad range of conservation issues including rehabilitation of threatened species, integrating climate change in wildlife planning, control of poaching and the management of tourism in wildlife areas.

Brighter future

For the one-horned rhino, it is hoped that drones will herald a decisive shift in the war on illegal hunting. Kaziranga has been fighting a long battle against those trying to kill the animals for their horns, which fetch huge prices in some Asian countries.

The main market for the horn is China where it is used to make medicine and jewellery, while in Vietnam many believe it has cancer-curing and aphrodisiac qualities.

Field training, Kaziranga National Park Source: TCS

The one-horned rhino species fell to near extinction in the early 1990s but has since been nurtured back to more stable numbers. It is currently listed as “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, one notch up from “endangered”.

If the use of these low-cost, high tech drones can help ensure the population’s continued recovery, it will serve as a model for wildlife conservation around the world.

This is a hugely exciting application of this emerging technology. I think you should link up with the Born Free Foundation. They have multiple case studies throughout the world that would build upon this work. Including a number of conservation projects in India eg Satpuda Tiger Reserves.

Look forward to seeing the results.